Chioggia represents the southernmost entrance to the Venice Lagoon and is the main fishing port in Italy, known for its excellent productivity in bulk cargo, exceptional loads, and passenger traffic.

Port in Numbers

The Port of Chioggia is located between the islands of Pellestrina and Sottomarina and serves as the southernmost entrance to the Venice Lagoon.

Access to the port is through a single entrance, the eponymous port mouth, with a width of 550 meters and a navigable depth of 8 meters below sea level.

It is estimated that there are 322 companies directly employed in Chioggia, and when combined with the 1,260 companies in Venice, there is a total of 21,175 employees.

The History of the Port of Chioggia

The Origins of Chioggia and Sottomarina

During the barbarian invasions in the 5th century, the two islands of Chioggia were used as a refuge for the Venetian population.

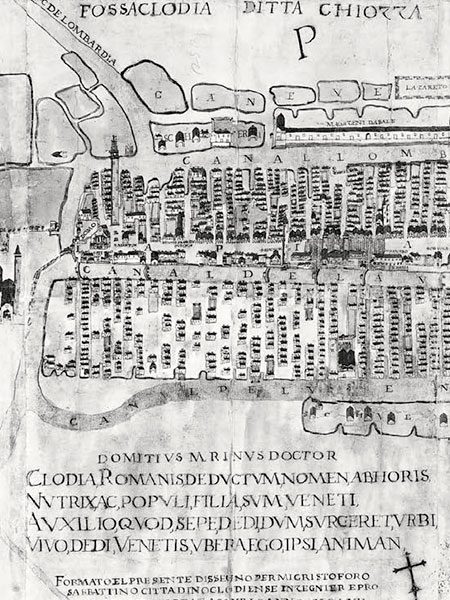

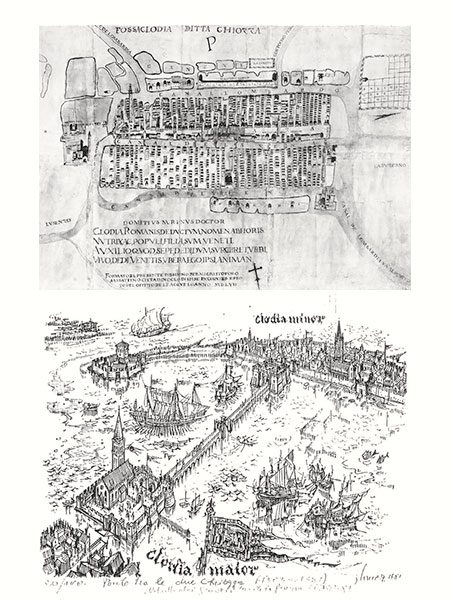

Chioggia and Sottomarina did not play a significant role in ancient times, although Pliny mentioned it as “fossa Clodia.” Local legend attributes its founding to a Clodio, but there are no certain sources confirming this.

The city’s name changed frequently, from Clodia to Cluza, Clugia, Chiozza, before finally adopting the name Chioggia.

The port’s importance explains the city’s growth and its significant development between the 11th and 12th centuries, during which it assumed the role of an important port city focused on trade, salt production, fishing, and other economic activities related to the sea.

This newfound importance led to Chioggia gaining attention from the neighboring Republic of Venice, which granted it administrative, managerial, and legal autonomy. This role was confirmed in the Pactum Clugiae, a document that ensured the city’s specific territory granted by the Republic’s government.

Between the 10th and 12th centuries, Chioggia assumed the role of a significant port city with recognized administrative, managerial, and legal autonomy granted by the Serenissima Republic.

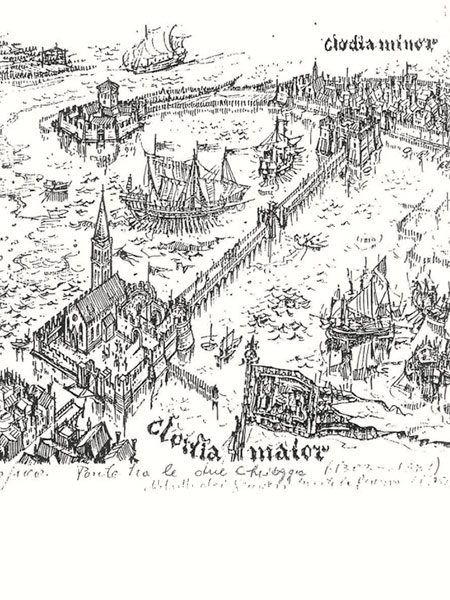

The Naval War of Chioggia

The proximity of the Serenissima Republic improved the dynamics of port activities, particularly seen in the improvements made to its maritime defense structures, as most threats arrived from the sea.

The Republic of Venice, in its aggression against the maritime trade of Chioggia, eventually pushed Chioggia into an alliance with Genoa. The economic rivalry between these two great medieval maritime republics was resolved only by the naval war of Chioggia in 1378, formally ending in 1381 with the Peace of Turin.

The maritime war, with Venice’s victory, subdued Chioggia’s commercial vitality for many centuries, reducing it to a fishing port, a salt producer, and limited trade with the Istrian and Dalmatian coast.

The Venetians immediately rebuilt the city and strengthened it with even more defensive structures, many designed by Michele Sanmicheli (1484-1559), who constructed walls and fortifications. These include the 14th-century Fort of San Felice.

Unlike Venice, Chioggia did not quickly recover its pre-war prosperity, and throughout the 15th century, it struggled to achieve economic, social, and demographic recovery.

The naval war of Chioggia (1378 – 1381) marked a significant historical turning point, transforming it from a “wealthy salt city” to a devastated and depopulated Chioggia.

The Renaissance of Chioggia and Maritime Trade in the Eastern Mediterranean

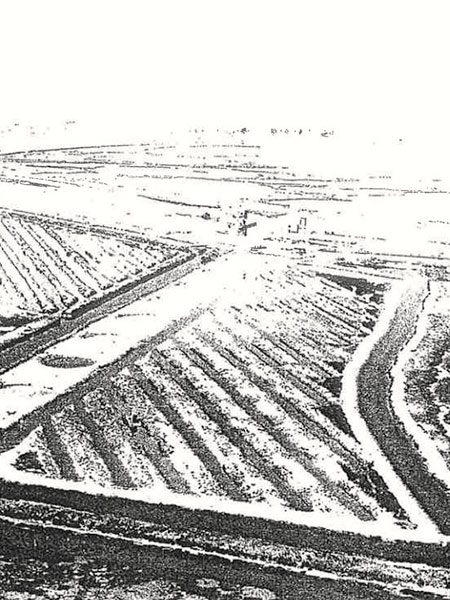

The city’s rebirth proved to be challenging, particularly due to the negative economic situation that affected Clugie salt production (produced in Chioggia). The number and size of the salt pans in Chioggia, which previously occupied extensive lagoon spaces, were reduced.

Lagoon fishing gained a much more important role than in the past, and at the same time, there was a growing propensity for maritime trade in the Eastern Mediterranean. Thanks to the increase in a well-equipped fleet, maritime trade became more intense and lucrative, following in the footsteps of the great merchants of the Venetian Republic.

The flourishing maritime trade and traffic in Chioggia during this period corresponded to the emergence of great navigators and merchants, including notable figures like Giovanni Caboto and Nicolò de’ Conti.

It is worth noting that boat construction has a long and illustrious tradition in Chioggia, historically represented in the prestigious “Mariegola dei Calafati“, a statute dating back to 1211, which is one of the oldest and most comprehensive corporate ordinances of arts and crafts in the communal period of Italy.

Lagoon fishing assumed an increasingly important role, and Chioggia intensified maritime trade in the Eastern Mediterranean, following the footsteps of the great merchants of the Venetian Republic.

From Decline with the Fall of Venice to Italy’s Leading Fishing Port

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Chioggia experienced another period of intense construction activity, particularly the reconstruction of old buildings such as the Cathedral and the Town Hall.

With the fall of Venice due to Napoleon, Chioggia came under French rule in 1797 and later Austrian rule until 1866 when it became part of the Kingdom of Italy.

The beginning of Venice’s decline as a powerful maritime republic marked the end of the Port of Chioggia.

Historically, fishing has been the mainstay of the port, but the Port of Chioggia, in addition to being Italy’s leading fishing port (second only to Mazara del Vallo), has achieved high levels of productivity and competitiveness in other sectors such as bulk cargo, exceptional loads, and passenger traffic with small cruise ships.

Today, Chioggia is Italy’s primary fishing port, known for its excellent productivity and competitiveness in bulk cargo, exceptional loads, and passenger traffic.

Discover the operators of the Port of Chioggia

SO.RI.MA

Impreport Coop.

K-Logistica

Holcim (Italia)

Chioggia Terminal Crociere

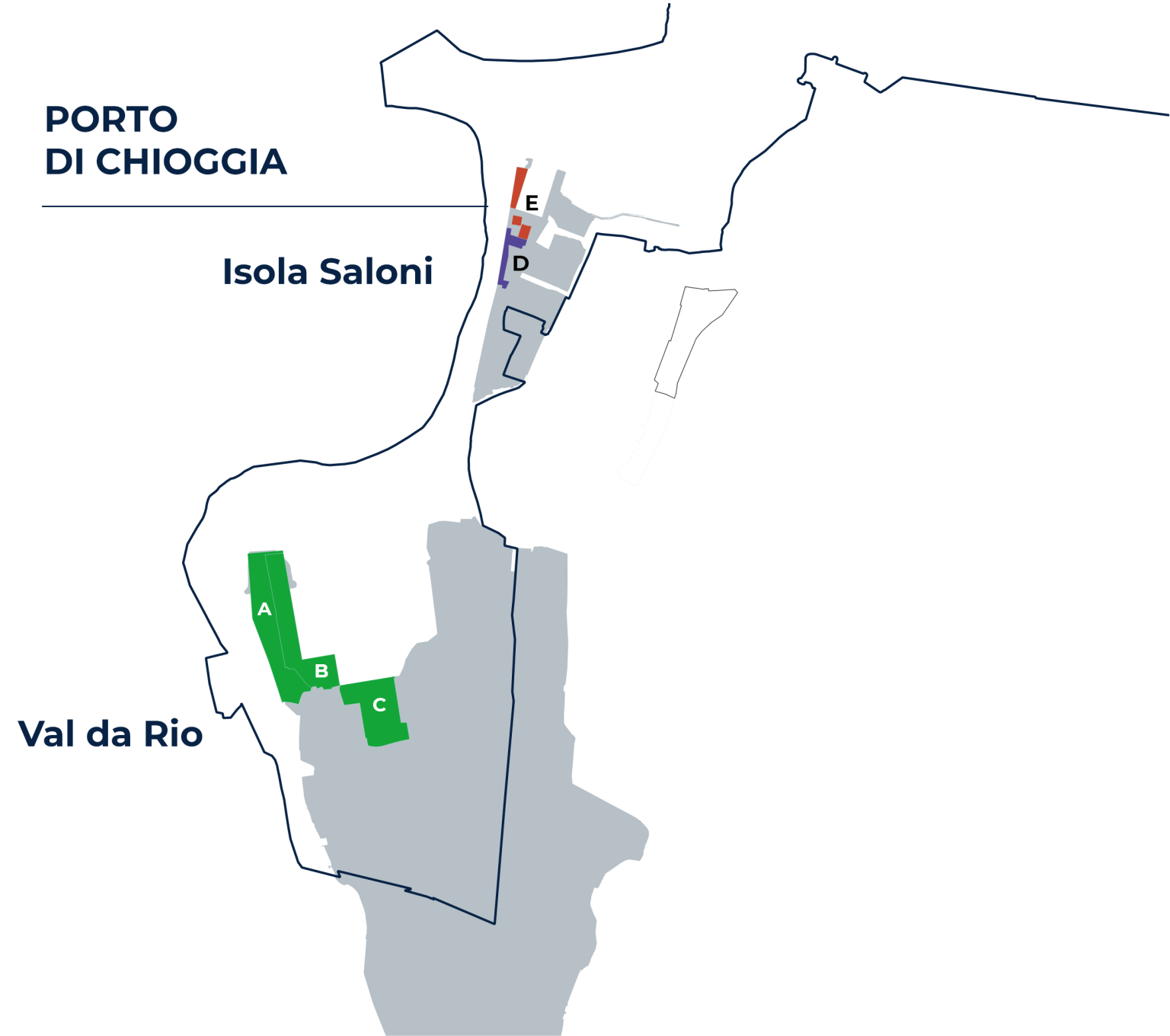

Commercial Terminals

- A. SO.RI.MA

- B. Impreport Coop.

- C. K-Logistica

Industrial Terminals

- D. Holcim (Italia)

Passenger Terminal

- E. Chioggia Terminal Crociere